Finding A Treasure

Originally published March 21, 2017

The two follow-up questions I’ve been asked my entire life:

“Is that a family name?”, and “Is your dad in the military?”

See, my first name sounds somewhat normal but always needs repeating. Multiple times, and usually followed with a “sounds like” clue. The military question comes up after people learn that in 10th grade I was starting my 11th school. By that time, I had lived in four different states and 12 different houses.

The best answer to both questions is, “No, my dad was just a hippie.”

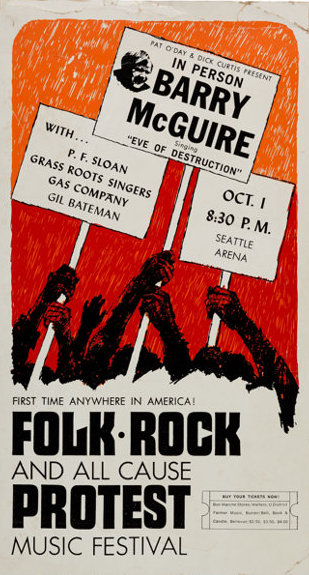

Now, I was probably too young to understand exactly what a hippie was in the 60s – and it’s not like he moved us to a commune or anything. I just know he grew his hair long, he played guitar, and in 1965 he performed at an anti-war rally in the Northwest.

In fact, Dad started his professional career as a musician. While attending Menlo College he played clubs in the San Francisco Bay Area and said he rubbed elbows with the future members of the Grateful Dead. He continued college in his hometown back in Seattle and mentioned that his band once jammed after hours with the band that the future legend Jimi Hendrix was playing in. He also starred as Conrad Birdie in the Seattle production of “Bye Bye Birdie” with Tom Poston and Patte Finley, who over the years were both regulars on “The Bob Newhart Show.”

He recorded a few 45s, including a local hit called “How to Do It” and a pre-grunge song called “My Daddy Walks in Darkness,” the latter of which my grandparents apparently hated. On that track, he spends the last half of the song literally screaming at the top of his lungs. When I learned of my father’s death last fall, I streamed the track and listened to the shrieking melody and it was surprisingly healing. It’s the sound I wanted to make but hadn’t let myself express. He was one of the most loving men you will ever meet. Even in the 70s and 80s he was the parent that kept custody of us four kids through two divorces.

In the weeks following his death, countless friends and colleagues of his “from the radio and record business” reached out to our family with heart-warming stories of how my dad was a kind soul amid this business.

Since making music didn’t always pay the bills, he wound up working for Jerden Records between gigs. The first album he ever worked on with the late producer Jerry Denon was “Louie Louie” by the Kingsman. In Rolling Stone’s 40th Anniversary Issue, that song made number five on the list of “Songs that Changed the World.”

I’m not sure how Dad wound up in New York from Seattle, but sometime around 1967 or 1968 he landed at Elektra Records in time for The Doors’ release of “Light My Fire.” I remember hearing it on the radio when I was in high school in the 80s, and him telling me that it was the first song over seven minutes long to ever make air on mainstream radio and that he helped make it happen. He told me about the time he wound up in the Playboy Mansion in Chicago one night where it was just him and Jim Morrison. These stories certainly captured my imagination as a teenager and made me believe with him that his next big break was just around the corner.

It’s crazy sometimes how our lives parallel our parents. I too was on the creative side of my business in film and video production but took a more traditional job that supports artists and their craft. However, I took the opposite path of my dad, staying put in one place with my family rather than moving around the country on to the next record label or interim job with hundreds of pounds of records in tow. I’m not sure how many he had, but I know each small box of records weighed about 15 pounds —and I hand-carried more than my fair share in and out of U-Hauls every year or so.

I loved looking through the album covers. Maybe we were running away from the angry mail carriers who delivered all those heavy boxes of records to him over the years. He was able keep all the albums he didn’t give out to radio stations and record stores, and each had a big stamp on it or a notch cut into the corner notating that the copy was “For Promotional Use Only. Not for Resale.”

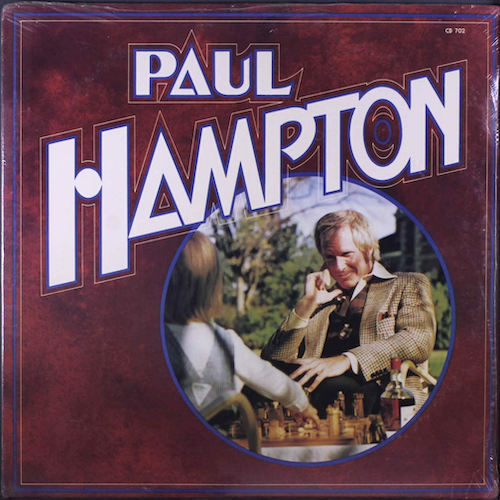

I even remember seeing myself on one of those covers, which is probably the reason that day is still vivid in my memory. I was only three or four and had the chance to go to work with my dad wearing my favorite pin striped overalls. I remember saying good-bye to my mom and jumping into the front seat of our 1973 Toyota Land Cruiser. I spent the morning on the grounds of the Boettcher Mansion in south Denver playing chess with a well-dressed man. The chess picture made the front cover of Paul Hampton’s “Resthome for Children”. A second shot made the back which was of me sitting on a chair with a blanket on my lap and reading a newspaper. You can’t see my face in either one, but I know it’s me.

By the last move, most of the records we lugged around with us had been abandoned, but my brother rescued a copy from obscurity for me from an old record store in town.

Elektra had other great artists at the time, such as Bread and Judy Collins, and business was good. In fact, “60 Minutes,” then in its second season, came to Elektra when they were at the top of their game to shoot a story on the record business. At my dad’s memorial, one of his friends mentioned the details of this event, so I dug through the CBS News archives on the Veritone Licensing site just to see if we might have even a text record mentioning it. I knew that it was sometime between 1968 and 1973 and it was on 60 Minutes. It literally took me 30 seconds to narrow my search to 60 Minutes assets between 1968 and 1974. From there I looked for the term “record” and found an asset called “60 Minutes: The Anatomy of a Record” that aired March 3, 1970.

I clicked on the preview, and lo and behold, about five minutes in there’s a scene of a marketing conference at Elektra Records in president Jac Holzman’s office. And there is my dad the hippie, sitting on the windowsill with his long hair among the swirling cigarette smoke. About a minute and a half into the clip he offers an explanation of Elektra’s release approach to the head of United Artists publishing. It’s hard to describe the feelings I had seeing my dad on TV at work at a time when I hadn’t even been born. It actually helped answer the question that I’ve always had and my kids probably wonder about me: what does my dad actually do for a living? Coincidentally, The Grammys were on the same night I found the clip, and Milt Okun, the record producer featured in the story, was also acknowledged during the “In Memoriam” video. My dad wasn’t famous enough to make the Grammy video but finding this treasure is a memory I’ll have forever. Love you dad.